DNA: being the same, being different

A thousand years from now, humans will have finally mastered how to get people from point A to point B without the use of a plane,...

A thousand years from now, humans will have finally mastered how to get people from point A to point B without the use of a plane, drastically reducing humanity’s carbon footprint and forever denying me the answer to “What’s the deal with airline food?” The teleportation process is easy enough to understand: you step into one machine in Vietnam; they disintegrate your body into billions and billions of pieces, keeping your unique DNA in an email; the other machine in, let’s say Northampton, receives that email, then uses some futuristic technologies to put everything back together. You open your eyes, and you’re in a new land, instantaneously. Perhaps in the year 3023, ethicality aside, scientists can even recreate historical figures from only a hair. Perhaps then, in Neo-Northampton, Francis Crick will one day have coffee at the Neo-Northampton Museum and Art Gallery, elaborating on how he and his colleague James Watson came up with the form of Life itself: The Double Helix.

To make a dish, one needs a recipe. To make an ÖRFJÄLL – a popular blue and white office swivel chair of IKEA, one needs an instruction manual (success varies). To make a human, one needs DNA. Remember the email that feeds into The Teleporter earlier? You would think that it would be huge, perhaps hundreds of terabytes worth of storage space, since our bodies are made up of more than three billion genetic pieces. I wouldn’t have asked if that was the case. By virtue of being the same species, all humans share 99% of their genome, which means that all humans are 99% genetically similar. Of those 3 billion pieces, only a tiny amount is unique to us, like your hair, your eyes, your skin, and your proneness to cancer.

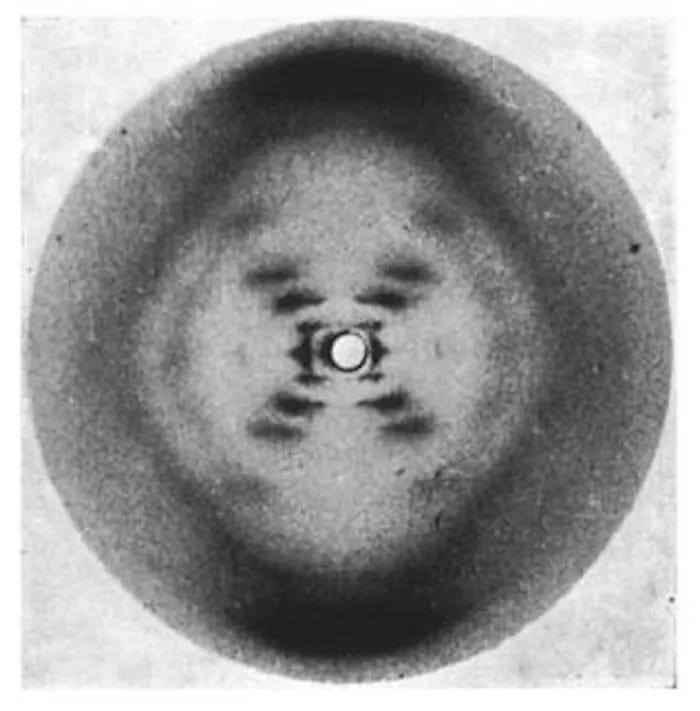

Cancer, yes, is also genetic. You have a higher chance of getting cancer if your parents/grandparents develop the disease. In the future, however, some company finally perfected the gene-editing tool CRISPR, racking in all the money in the world, and winning the team of doctors behind it a Nobel Prize. In the acceptance speech, after thanking their friends and families, the team of doctors would give tribute to Crick and Watson, who discovered the model of the DNA in April 25th, 1953 (The acceptance speech, of course, happened before Crick is resurrected). By now, everyone and their cancer-free grandmother knows the twisted, extendable ladder that is DNA. Crick, in 1953, had this to go off of:

Source: https://www.forbes.com/sites/evaamsen/2019/04/25/what-does-dna-look-like-after-66-years-were-still-learning-more

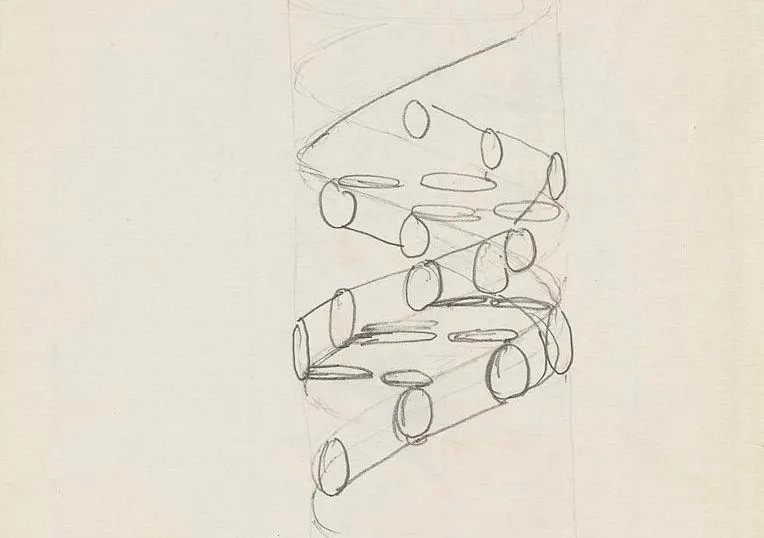

Through sheer brilliance and a little genuity with some cardboard cut-outs they found laying around, the pair came up with this

Source: https://www.forbes.com/sites/evaamsen/2019/04/25/what-does-dna-look-like-after-66-years-were-still-learning-more

and eventually the Double Helix we know and love. The steps of the DNA ladder consist of the small chemical bases: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine, abbreviated A, T, C, and G, respectively. Only the pairs of either A:T or C:G fit as rungs, between the two siderails.

Going to the U.K. was a spur-of-the-moment kind of thought. I arrived at Northampton, hometown of Crick, a little bit after 7p.m, when night had settled peacefully. At the entrance to Town Centre on Abington Street, I slowly sank into a bench next to the “Discovery” Sculpture. It was the First of November, one day after I landed. Coming from Ho Chi Minh City, where I would put on blankets if the temperature dipped below 30, the cold condensed my loneliness into snakes, their fangs snapping at each memory of home. Nothing about the sculpture stood out to me as interesting, as I assumed it was only another piece of public art that was strewn around town, another desperate attempt to draw in visitors. The place did not seem like anyone’s first choice, certainly wasn’t mine, I chose the University there because it was one of the more affordable options. Yet, as if hypnotized, I removed my backpack and glove to have a closer look at the rising beams. Breathless from the wind, I could hardly recognize my reflection on the metallic surface, and the snakes finally attacked.

The subject of race and sex runs through my mind often, like Batman and Joker. If 99% of us are the same, then what was the point of race, of sex, of those thousand phrases that humans used to look down on others? Have we created those phrases because we all crave an identity, so much so that we put it on someone else rather than facing the truth? Deep down, do we realiza that an Asian’s A(denine) (haha) is exactly the same as an Englishwoman’s? And have we come up with different terms of sexuality because we are obsessed with being politically correct? Is it so important to be different?

“Alien” is the legal term for a person who is not a citizen or a national of a specific country. If there is a word more fitting to describe myself, I have not found it. All my life, I have wondered whether where I would fit anywhere on this planet, because the idea of myself being human seem so absurd. In the macro level, everything seems to be in order: I have two eyes, two ears, a mouth, a nose - bigger than I would have liked like, but nothing too out of the ordinary, legs, hands... Could it be, then, this estranged feeling comes somewhere on the micro level, something unseeable, something missing or out of place, a piece of mutated DNA. A mutation occurs when even one of the letters in the three-billion sequence went rogue, perhaps a T appears where an A should be. Much of the time, mutations do not have any impact on the human body. But other times, it can be devastating. Sometimes, it leads to cancer. Other time, it creates an Alien.

“E” (for English), must have lodged itself into my DNA sequence and caused said mutation. I know full-well how it happened, too. Imagine, if someone came up to you on the street and offered to splice you in half, you’d run away without a second thought. Even if that someone is your doctor, and it’s for some perfectly sound medical reasons, you would still have to pause and think. But since it was from my parents, at such a young age for one to even know of the word “refuse,” it was inevitable. And thus, my developing young mind forever diverged, two strands of thoughts, one Vietnamese and one English, in a constant battle, twisting themselves together into a violent spiral, into the double helix.

Tet has always been a struggle for me growing up. Every year in February, families would gather to celebrate the biggest traditional holiday of the country. Every year, I would sit and pray for the dinners to pass. To the adults, I was always the “white-washed” kid who knew nothing about traditions. I was barely able to use the chopsticks, since the American movies they would play at the English Centre always have characters with spoon, forks, and knives. As a kid, I thought using knives was the most elegant thing, and that thought single-handedly brought guilt, embarrassment, and shame whenever an uncle would mention how slow I was eating my noodle. Then there was the look of my parents, and the awkward laughter to try and save the situation.

At least Tet only lasts a few days. School, however, lasts 18 years. The attacks were worse and constant. When I couldn’t find the correct words in Vietnamese to express myself, or when I accidentally blurted out an English word I learned in a book. “Stop looking at me,” I thought, and the flushed cheeks and sweaty palms make conversations harder and laughter louder. The two sensations blend to one haunting feeling, and throughout my teenage years, that feeling grew to the point of a full-on anxiety attack whenever I am engaged in talks.

Gasping for air, a hand brought me back into the present. It was a good Samaritan checking if I was doing okay. I nodded and said thank you. The painful zap to the past, however, did me some good: I was reminded that I chose, for myself, to study English Literature here in the UK, and that it creates an opportunity for myself to truly embrace my passion. As I raised my head and look at myself, I felt the vipers loosen their grips, and the toxin drained.

Caressing one beam, I reach for the other strand of DNA, of Vietnam, of the past. The analogy of the DNA double helix strikes me as a fitting way of representing the dual aspects of my life as both an Information Security Analyst and a writer. There is nothing wrong with being a writer and an IT guy at the same time, but it appears that having a creative brain and being mathematically adequate, or even having anything at all to do with Math, is considered paradoxical in society. This definition and resemblance appear to best reflect the hybrid identity that I possesses and its inherent dissonance and tension. I exist within both worlds – pragmatism and creative writing – and both are intrinsic within me, comprising my unique self and my own point of view. In an interview, Lucy Glendinning, the creator of “Discovery,” said the statue was built in such a way that different angles of viewing results in different results. When view in 3D, the model of DNA shows two parallel rods never meeting each other. Yet, in 2D, there is always a convergence. And that convergence for me was Northampton.

The ultimate goal of my trip to the UK is book publication. Without knowing if I was good enough, or ever will be good enough, I left a comfort job at home for the unknown. My portfolio until then included stories of the constant arguments of my parents because I could not perform in schools, the snail with crushed shell I saw on the way home, and of Gods and heroes. But in Vietnam, to be a writer means to die in poverty. As the joke goes, a homeless guy would probably have to donate to me if I pick up a quill instead of a “real job.” And thus, the UK, where my favorite authors are based.

After the initial culture shock, Northampton turned out to be amazing for a writer. New students would often talk about having nothing to do here; or how the town centre is quite ugly; or a myriads of complains around how they bore they are and how they want to leave as soon as their courses are finished. There are truths to those statements. Yes, the town’s bars are lame, yes, the centre is not much to look at with two huge construction sites smackdabbed in the middle, yes, people don’t come out much, and yes, there are only so many times you can eat out with your friends at the same restaurant until you’re sick of the food. But jokes on them, I am quite content with staying in my room all day, with seeing the beautiful rivers and forests around town that simply didn’t exist in Ho Chi Minh City, with going to the University’s library to borrow books, with everything being so quiet I can hear myself think. And it’s only an hour away from London by train!

Quan điểm - Tranh luận

/quan-diem-tranh-luan

Bài viết nổi bật khác

- Hot nhất

- Mới nhất