[Day 6] Learning how to learn - Week 2

Photo by Patrick Fore on Unsplash Introduction Learning how to learn , released from 2014, is a famous MOOC course on Coursera.com....

Photo by Patrick Fore on Unsplash

Introduction

Learning how to learn, released from 2014, is a famous MOOC course on Coursera.com. This course is instructed by Dr Barbara Oakley and Dr Terrence Sejnowski, both of them have a solid background on neuroscience and learning methods. During four weeks in this course, two instructors taught about the human brain, different modes of thinking and ways to improve their learning. Consequently, they can apply these techniques to help them pass classes, learn a new language, write faster, sharpen their problem-solving skill, etc.

WEEK 2 — Chunking

What is a chunk?

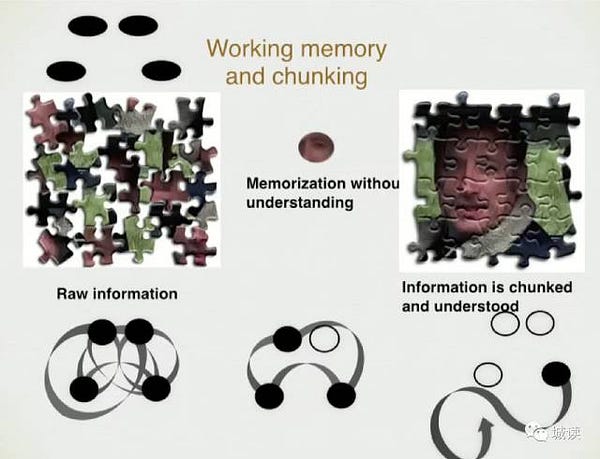

Chunking is the mental leap that helps you unite bits of information into the new logical meaning so that it easier to remember and also easier to fit into the larger picture of what you’re learning. We can not memorise a fact if we don’t know HOW to use it (Chunk) and WHEN to use it (Context). Your brain has to stay in Focused mode to create chunks. That’s why we can not work right when we are in stress.

Source: https://mp.weixin.qq.com

Chunk is a piece of information, bounding together like a .zip file. The complex neural activity that ties together our simplifying abstract chunks of thought. For example, when you first learn the word “mama” from your mother, your neurons fire and wire together in a shimmering mental loop cementing the relationship in your mind between the sound “mama” and your mother’s smiling face. The concept of neural chunks also applies to sports, music, academic topics and any knowledge humans can gain. The path to becoming a master is built little by little; small chunks can grow larger as you gradually become a master of the material. Once you chunk an idea, you don’t need to remember all the little details because you have gained the map.

How to form a chunk?

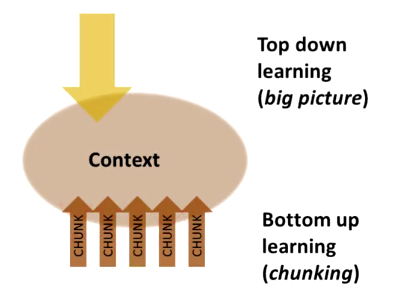

The first step on chunking is to focus your undivided attention on the information you want to chunk. Next, you have to understand the basic idea you’re trying to chunk. Understanding is like a super glue that helps hold the underlying memory traces together. For example, in math and science related subjects, closing the book and testing yourself on whether you can solve the problem you think you understand, rather than just looking at the answer of someone else, will speed up your learning at this stage. But understanding is not enough, that’s why we need a “context”. The third step to chunking is gaining context, so you can see not just how but also when to use this chunk. By repeating and practising with both related and unrelated problems, you can see not only when to use the chunk but when not to use it.

Learning involves two processes, bottom-up, the practice and repetition that help you both build and strengthen each chunk to retrieve later on, and top-down, which allows you to see what you’re learning and where it fits in. For instance, doing a fast two-minute picture walk through a chapter in a book before you begin studying it (top-down) allow you to gain the big picture, after that, you can fill in all the details (bottom-up).

Illusions of Competence

- Rereading. Rather, try to recall from the material you’ve just read by simply looking away and visualising the main idea. The retrieval process itself enhances deep learning and helps us to begin forming chunks.

- Drawing concept maps before understanding the meaning. It’s like trying to learn advanced strategy in chess before you even understand the basic concepts of how the pieces move.

- Watching others solving problems. Merely glancing at a solution by someone and thinking you truly know almost do nothing to knit those concepts into your underlying neural circuitry. The key is that you are the one doing the problem solving to master the idea.

- Highlight and underline too much. Instead, try to look for main ideas before making any marks and keep your underlining or highlighting to a minimum.

Powerful tools

- Recalling material when you are outside your usual place of study. In reality, you often take tests in a room that’s different from the room you were learning in. By recalling and thinking about the material when you are in a various physical environment, you become independent of the cues from any given location, helping you avoid the strange problems.

- Mini-testing. Finding a mistake in what you are doing is very valuable before high stakes real tests, because they allow you to make repairs bit by bit so that you can learn better and do better.

What motivates you?

Your brain has a set of diffusely projecting systems of neuromodulators that carry information, not about the content of experience but its importance and value to your future. Neuromodulators are chemicals that influence how a neuron responds to other neurons, and there are three of them that affect your motivations: acetylcholine, dopamine, and serotonin.

- Acetylcholine neurons form neuromodulatory connections to the cortex that are particularly important for focused learning when you are paying close attention.

- Dopamine neurons are part of brain system that controls reward learning. Dopamine is released from these neurons when we receive an unexpected reward. When you promise to treat yourself something after a study section, you are tapping into your dopamine system. Loss of dopamine neurons leads to a lack of motivation and interest in things that once gave you pleasure.

- Serotonin is a third diffuse neuromodulatory system that strongly affects your social life. Lacking serotonin can lead to depression or crime. Prozac, which is prescribed for clinical depression, raises the level of serotonin activity. Inmates in jail for violent crimes have some of the lowest levels of serotonin activity in society.

Finally, your emotions strongly affect learning as you are well aware. They are intertwined with perception and attention and interact with learning and memory. The amygdala, an almond-shaped structure nestled down at the base of the brain, involves in processing memory and decision-making as well as regulating emotional reactions. You will want to keep your amygdala happy to be an effective learner.

The Value of a Library of Chunks

What people usually do to enhance their knowledge and gain expertise, is to build the number of chunks in their mind gradually. The bigger and more well-practised your chunked mental library, the more easily you’ll be able to solve problems and figure out solutions. Chunks can also help you understand new concepts, because one new chunk can be surprisingly related to similar chunks, not only in that field but also in different fields. This idea is called transfer.

You’ll find that once you put that first problem or concept in your mental library, whatever it is, then the second concept will go in a little more smoothly and the third more easily still.

If you have a library of concepts and solutions internalised as chunked patterns, you can easily skip to the right solution by listening to whispers from your diffuse mode. Your diffuse mode can help you connect two or more chunks in new ways to solve novel problems.

Solving problems

There are two ways to figure something out or to solve problems:

- Sequential thinking where each small step leads deliberately towards a solution involves the focused mode.

- Intuition on the other hand often seems to require this creative diffuse mode linking of several seemingly different focused mode thoughts.

Most difficult problems and concepts are usually grasped through intuition because these new ideas leap away from what you’re familiar. Keep in mind that the solutions the diffuse mode provides should be very carefully verified using the focused mode. Intuitive insights aren’t always correct.

Overlearning

Overlearning is continuing to study or practice after you’ve mastered. It can be especially valuable if you choke on tests or public speaking. Automaticity can indeed be helpful in times of nervousness, but be wary of repetitive overlearning during a single session as it can be a waste of valuable learning time.

Deliberate practice

Repeating something you already know perfectly can also bring the illusion of competence that you’ve mastered the full range of material when you’ve actually only mastered the easy stuff. Instead, you should focus on the more difficult material. This method is called deliberate practice. It’s often what makes the difference between a good student and a great student.

Einstellung

Einstellung, which is a German word means mindset, reminds you about a kind of the wrong approach, which means your initial intuition about what’s happening or what you need to be doing is misleading. You have to unlearn your erroneous older ideas or approaches before you can learn new ones.

Interleaving

Mastering a new subject means learning not only the basic chunks but also learning how to select and use different chunks. The best way to learn that is by practising jumping back and forth between problems or situations that require different techniques or strategies. This is called interleaving.

Once you have the basic idea of the technique during your study session, say, learning to ride a bike with training wheels, start interleaving your practice with different types of problems, approaches, concepts and procedures. Particularly, you can look ahead at the more varied math or science problem sets at the end of chapters, or you can deliberately try to make yourself occasionally pick out why some problems call for one technique as opposed to another.

Interleaving is extraordinarily important. Although practice and repetition are important in helping build solid neural patterns, it’s interleaving that builds flexibility, creativity and independent thinking. When you interleave between several subjects or disciplines, you can easily make interesting new connections between chunks in the different fields.

There’s sometimes a trade-off to develop solid chunks of knowledge in different fields. Developing expertise in several fields mean that your expertise in one field or the other isn’t quite as deep as that of the person who specializes in only one discipline. On the other hand, if you develop expertise in only one discipline, you may become more deeply entrenched in your familiar way of thinking and not be able to handle new ideas. Philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn discovered that most paradigm shifts in science are brought about either young people or polymaths, who are not so easily trapped by Einstellung, blocked thoughts due to their preceding training.

Takeaway notes from Dr Norman Fortenberry — Learning at MIT:

- Be a part of a group and making the connections to the people who have the resources that you need to succeed.

- Breaks involve total mental turn-off

- Internalize material you have been taught

- Take every challenge in peer discussions and tutoring, or Rebut yourself

Takeaway notes from Scott Young (He compressed four-year MIT curriculum for Computer Science into one-year independent learning. He is now learning four different languages, Spanish, Portuguese, Chinese, and Korean)

- Active learning by getting into problems as quick as possible.

- Important parts of a MOOC course: problem sets, reading list and accompanying textbook.

- Learn more by studying less, staying focus and testing frequently.

Thank you so much for reading this post.

I'm working on writing and this 30-day journey is my first project. I would really appreciate if you could leave your feedback and comments on how I can further improve. I will be creating more posts in future about my experiences and projects.

I'm working on writing and this 30-day journey is my first project. I would really appreciate if you could leave your feedback and comments on how I can further improve. I will be creating more posts in future about my experiences and projects.

English Zone

/english-zone

Bài viết nổi bật khác

- Hot nhất

- Mới nhất